This article first appeared on the Promising Practices in Refugee Education website.

By Madeeha Ansari

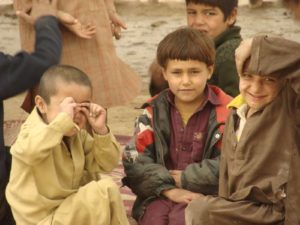

How do refugee children live?

Often, the image that comes to mind if asked that question is of a settlement like Jalozai camp in Pakistan, with rows of tents sectioned by UNHCR canvas sheets. Or what is now the sprawling Dadaab refugee complex in Kenya – or the newer Zaatari camp in Jordan, with pre-fab containers dotting the desert. A refugee camp is a world in itself, involving stakeholders from aid agencies to national and local governments, to the communities who find themselves adjusting to a new ecosystem, while dreaming of a home they may not see again.

In reality, only a small fraction of people who are forcibly displaced live in formal camps. In Pakistan, for instance, about 90 percent of displaced persons live outside camp situations[i]; and only one fifth of Syrian refugees in Jordan live in Zaatari camp.[ii]

In 2016, the UNHCR estimated that 60 percent of refugees were living in urban areas.[iii] This does not include those who are unregistered, uncounted and unseen. Many urban refugees choose to don invisibility, in order to live and work in cities which do not “officially” have a place for them. This invisibility brings with it both risks and challenges; without legal protection, entire communities are vulnerable to exploitation, and fall through the cracks of basic services like water, sanitation, health – and education.

Hard choices – a story

One illustrative story is from a network of non-formal, open air schools in the slums of Islamabad, Pakistan. A few years ago, a local cleric began to play on the fears of an Afghan refugee settlement, and slowly began expanding his mosque boundaries into the space where the school shed was set up. Not only did he use religion to rouse support for replacing the school with a madrassa,[iv] he also used his connections with the police to threaten families that had neither national identity cards, nor legal entitlement to the land on which they had lived for years. A traditional jirga meeting was called to vote on whether the refugee school would stay, or the cleric would prevail.

This was, in essence, a vote to decide the fate of the refugee children in the squatter community who lived hidden from view, behind the railway lines on the edge of the city. Like other children on the move, entering urban poverty, many of them had to choose between work and school at an early age. Those exposed to the streets faced the risks of abuse and neglect, and the threat of recruitment by criminal or militant gangs. The bridge school worked around their reality, representing a space where they could imagine a different future.

Ultimately, the promise of a better life for children drowned out the voices of fear and anger at the jirga. The community took the decision to retain and protect the refugee school, and even to build a covered space where older girls could continue to learn.

Cities for children

While that day at the jirga was a victory for education and for the refugee children of the community, for urban refugees every day, life is characterised by uncertainty. For those lacking legal status, there is a constant threat of being made to move by municipal authorities. Formal development and humanitarian organisations, too, have been slow to engage with off-camp displaced populations, so they have few channels to access for support.

At Cities for Children, we believe that every child has the “right to a childhood” – the right to read, play and feel safe. That is why we partner with institutions like the Pehli Kiran School System (PKSS), that offers education to under-served urban communities like the Afghan refugees in our story. For us, even basic, open-air sheds represent oases of learning opportunities, where children can be protected from the harsh realities of the streets.

In line with recommendations in the Promising Practices in Refugee Education, we believe that learning and wellbeing go hand in hand. To this end we have been working to build the capacity of street-working staff to recognise mental health risks and offer psychosocial support. In addition, we work with volunteer networks to design and implement structured recreation programmes, because we believe that happy memories build resilience. This way, we hope to engage entire communities, and motivate them to keep sending their children to school.

If cities are growing, so is a whole generation of refugee young people, who will be shaping the world of tomorrow. It is important to see them, to count them, and to recognise the potential they have to paint a different picture for themselves and their families.

[i] IRIN, “Negative Coping Strategies Among Pakistan’s IDPs,” Reliefweb, August 05, 2013. Online.

[ii] Kingsley, Patrick. “Refugee Camp: Our Desert Home Review – Step inside the World’s Largest Sanctuary for Syrians.” The Guardian, July 22, 2016. Online.

[iii] UNHCR 2016, Global Trends: Forced Displacement in 2015. pp 20.

[iv] School for religious instruction